How fast does a plucked guitar string move? It’s a complete blur, so surely it’s travelling at a terrific speed. 50 miles per hour? 100 miles per hour? What do you think?

!["Vibrating guitar string" by jar [0] is licensed under CC BY 2.0](https://bencraven.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Vibrating-guitar-string-1024x850.jpg)

Walking pace. A typical speed for the middle of a guitar string given a good twang is walking pace. And that’s the middle of the string. Near its ends, it’ll be moving much more slowly.

How can that be so? Well, although the string is going back and forth hundreds of times a second, it’s only travelling a few millimetres on each trip. So the distance that it travels in each second isn’t as much as you might expect. It certainly isn’t as far as I expected.

If you think that the string moves slowly, what about the body of the guitar? The string itself radiates very little sound into the air; its job is to set the body of the guitar vibrating. The body of the guitar, with its much larger area, is much more effective than the string at setting air into motion. Yet we can’t even see the body vibrating. At what snail’s pace must it be moving?

Remember also that the air molecules on which the guitar body acts are already travelling at something like 500 metres per second. Isn’t it astonishing that the sub-pedestrian movements of the guitar affect the movement of the air molecules enough to produce a sound that we can easily hear?

The calculation

Suppose that we look near the centre of the string, where its movement is the greatest. Shortly after being plucked, the width of the blur that we see is going to be something like 5 mm. So for every complete oscillation, the string does a round trip of about 10 mm.

The frequencies of the strings on a standard 6-string acoustic guitar are (to the nearest whole number) 82, 110, 147, 196, 247 and 330 hertz (one hertz is one oscillation per second). If we multiply these frequencies by the 10 mm round trip, it tells us how far the centre of each string travels in one second, that is, its average speed. I’ve converted these speeds into metres per second. For comparison, a brisk walk at 4 mph is about 1.8 ms-1.

| Note name | Mean speed of middle of string in metres per second (to 2 sig. fig.) |

|---|---|

| E | 0.82 |

| A | 1.1 |

| D | 1.5 |

| G | 2.0 |

| B | 2.5 |

| E | 3.3 |

Our brisk walk is right in the middle of this range. And remember, we’ve done the calculation for the part of each string that’s moving the most. Near its ends, each string will be moving much more slowly than this.

Complication 1 – how long is the round trip really?

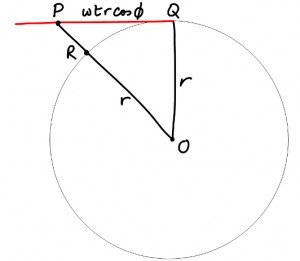

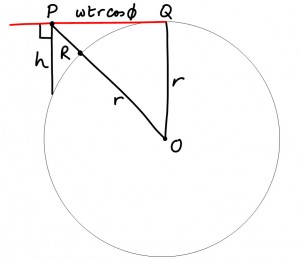

So far, we’ve assumed that each part of the string does a simple back-and-forth movement along a straight line, but if you carefully watch a vibrating guitar string you’ll see that the string often moves in an irregular but roughly elliptical orbit. The wire-wound lower strings show this most clearly; you can see a hint of it in the image at the top. This makes the round-trip distance a bit longer than the 10 mm that we used in the calculation earlier. Does this affect the string’s average speed much?

We’ll take the extreme case where each part of the string moves at constant speed in a circle of diameter 5 mm rather than along a straight line 5 mm long. The circumference of this circle will be ![]() mm, or about 15 mm. So the speeds of the strings (in this rather unlikely extreme case) will be about 50% greater than the ones listed above. They are still hardly impressive.

mm, or about 15 mm. So the speeds of the strings (in this rather unlikely extreme case) will be about 50% greater than the ones listed above. They are still hardly impressive.

Complication 2 – the peak speed

So far, we’ve calculated the mean (average) speed of the string over its round trip. However, unless it’s moving in a perfect circle, its speed changes constantly, and its peak speed will be higher than its mean speed. How much higher?

Imagine that part of the string is vibrating back and forth along a straight line in the simplest possible way. At one end of the movement the string is stationary as it changes direction. It then speeds up, reaching its peak speed at the centre of its range of movement. Then it slows down until it reaches a halt again at the other end of the movement and changes direction again. How do we calculate the peak speed if we know the time taken for the round trip?

You’ll need to know a bit of maths for the next bit. The simplest vibration of the string is where each part undergoes simple harmonic motion, that is, where its position varies sinusoidally with time. This means in turn that the velocity of the string also varies sinusoidally in time. So we need to ask: how does the mean value of a sinusoid compare to its peak value?

Consider the function

Consider the function ![]() , for half a cycle, that is, for theta from

, for half a cycle, that is, for theta from ![]() to

to ![]() radians. We construct a rectangle between these limits, such the rectangle’s area equals the area under the sine curve. The mean value of the sine function is the height of the rectangle, which its area divided by its width (which is

radians. We construct a rectangle between these limits, such the rectangle’s area equals the area under the sine curve. The mean value of the sine function is the height of the rectangle, which its area divided by its width (which is ![]() ). So we need to work out the area

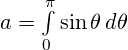

). So we need to work out the area ![]() under the sine curve between

under the sine curve between ![]() and

and ![]() , which we can do by integration:

, which we can do by integration:

![]()

![]()

![]()

We constructed the rectangle to have area ![]() . Its width is

. Its width is ![]() , so its height, and therefore the mean value of the sine function, is

, so its height, and therefore the mean value of the sine function, is ![]() . The height to the peak of the sine curve is 1, so the peak value of the sine function is

. The height to the peak of the sine curve is 1, so the peak value of the sine function is ![]() times its mean value. This means that the peak speed of our guitar string is

times its mean value. This means that the peak speed of our guitar string is ![]() times, or 50% more than, its average speed. Again, nothing to write home about.

times, or 50% more than, its average speed. Again, nothing to write home about.

(Rather pleasingly, this ratio of ![]() is the same ratio that we got earlier in Complication 1. It means that the peak speed of a particle doing simple harmonic motion with a given amplitude

is the same ratio that we got earlier in Complication 1. It means that the peak speed of a particle doing simple harmonic motion with a given amplitude ![]() and period

and period ![]() is exactly the same as the (constant) speed of a particle moving in a circular orbit of radius

is exactly the same as the (constant) speed of a particle moving in a circular orbit of radius ![]() with period

with period ![]() . This isn’t a coincidence. It arises because the circular motion can be considered as two linear simple harmonic motions at right angles to each other.)

. This isn’t a coincidence. It arises because the circular motion can be considered as two linear simple harmonic motions at right angles to each other.)

Credits

“Vibrating guitar string” by jar [0] is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Mathematical typesetting by QuickLaTeX